Thursday, 27 August 2009

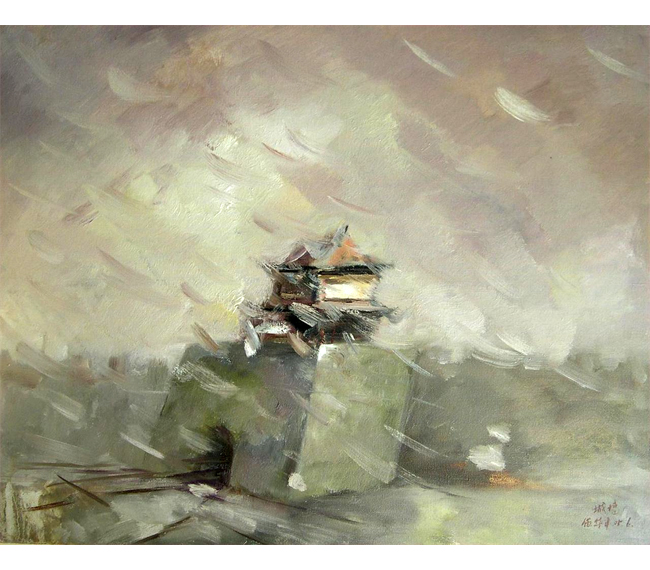

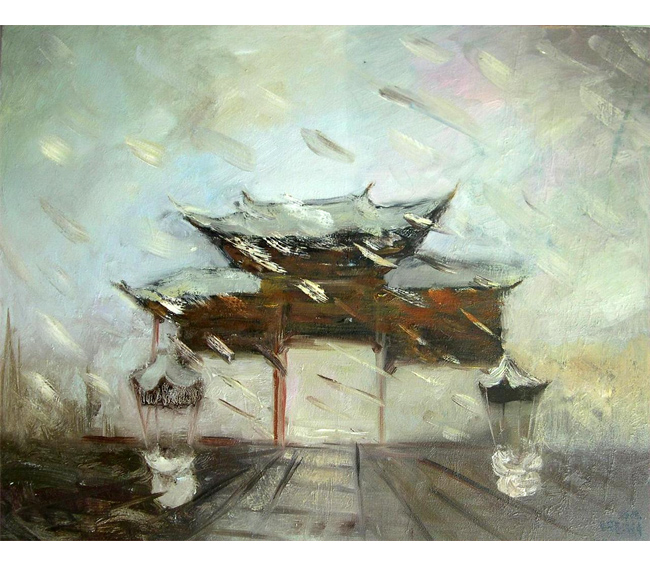

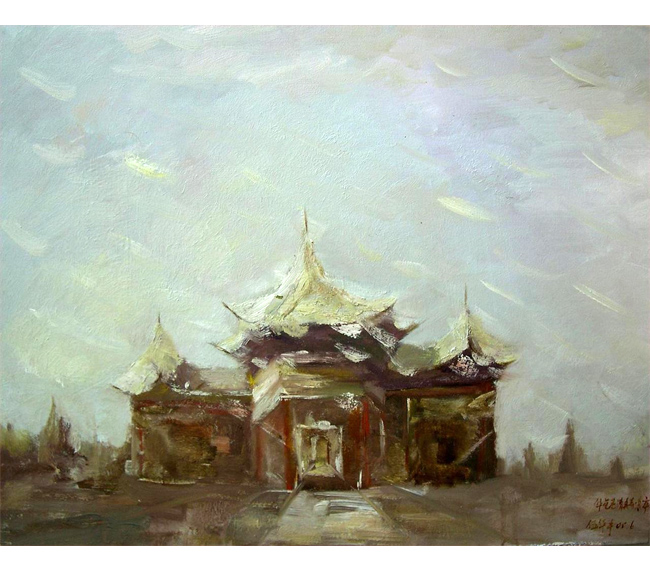

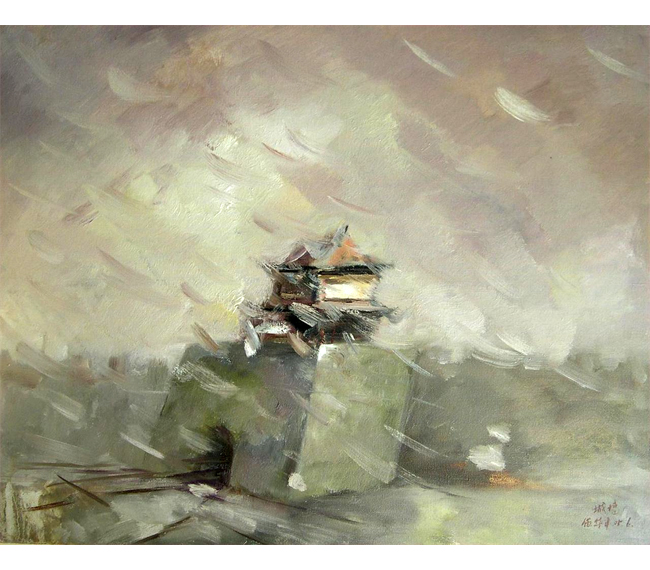

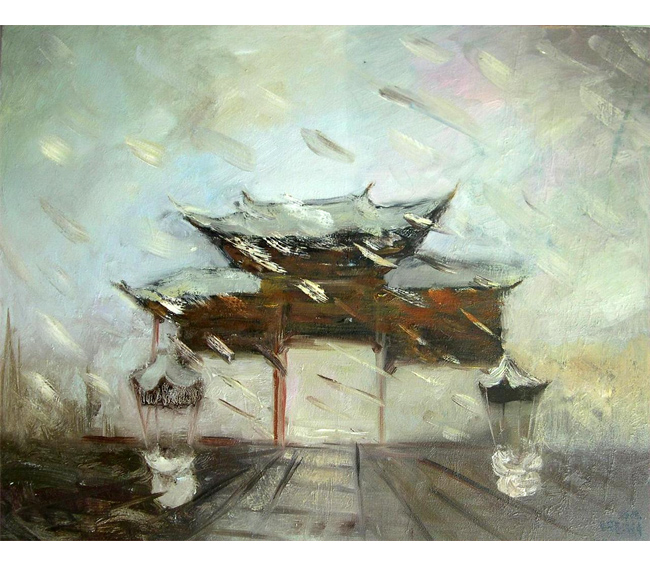

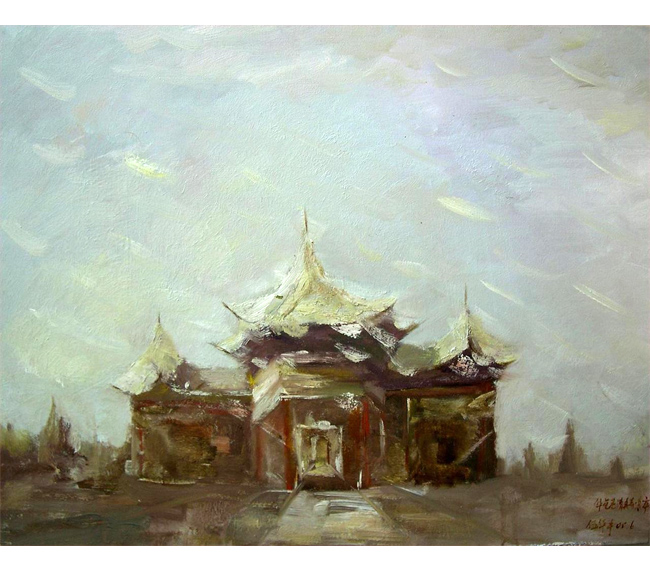

When I was young, I practiced painting. It was a natural extension from Chinese calligraphy. I remember being fascinated with beautifully “watery” paintings of landscapes, wildlife and buildings produced by ancient Chinese masters, and I certainly tried very hard to mimic the natural flow of brush strokes common in many Chinese paintings, but often with mixed results. It was very easy to convey movement in a picture if one had good control of the brush. It did not help that the watercolour paints were, more often than not, diluted excessively to achieve that soft, faint “watery” look. So, of course, when I came across Wu HuaFeng’s works, I was somewhat taken aback. They allude to ancient China, yet are done with thick oil paints and very short, harsh strokes, ultimately imparting a rather European aesthetic to otherwise distinctly oriental structures…

Tags: Art, China, Painting

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Wednesday, 26 August 2009

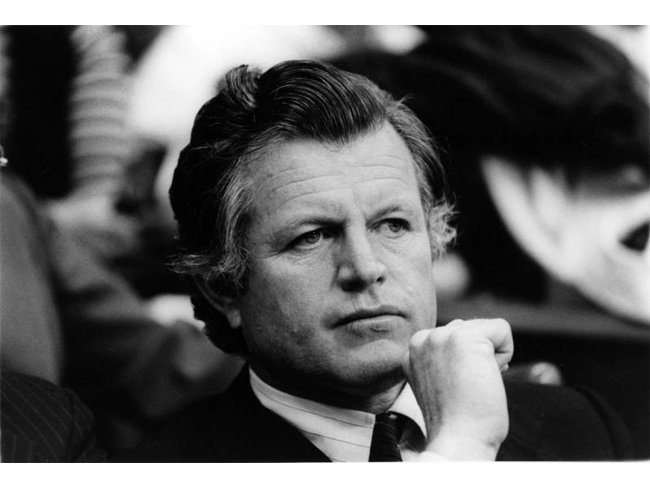

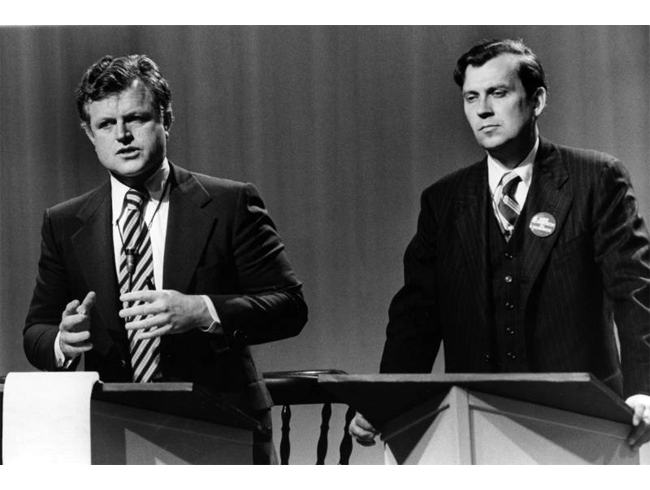

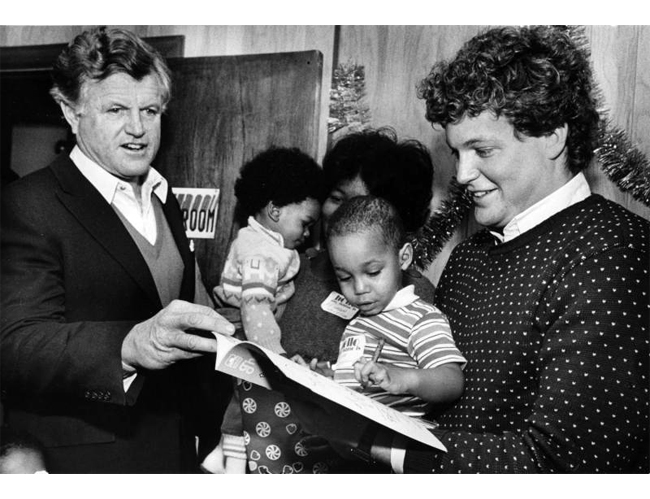

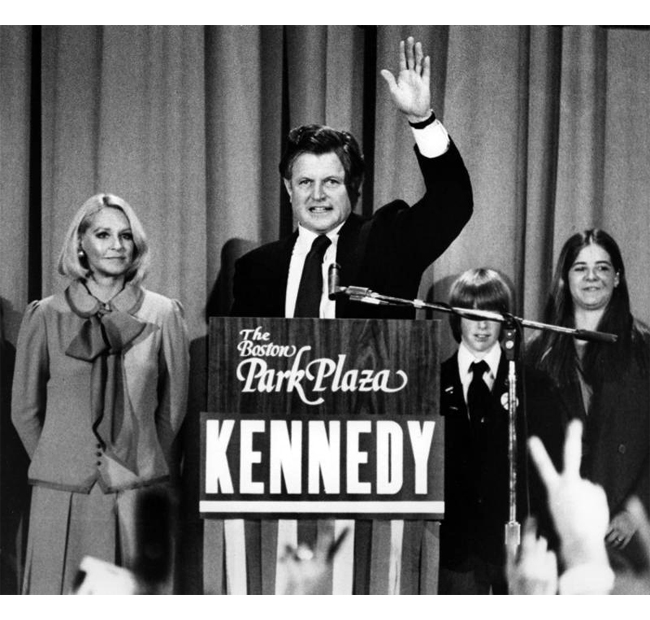

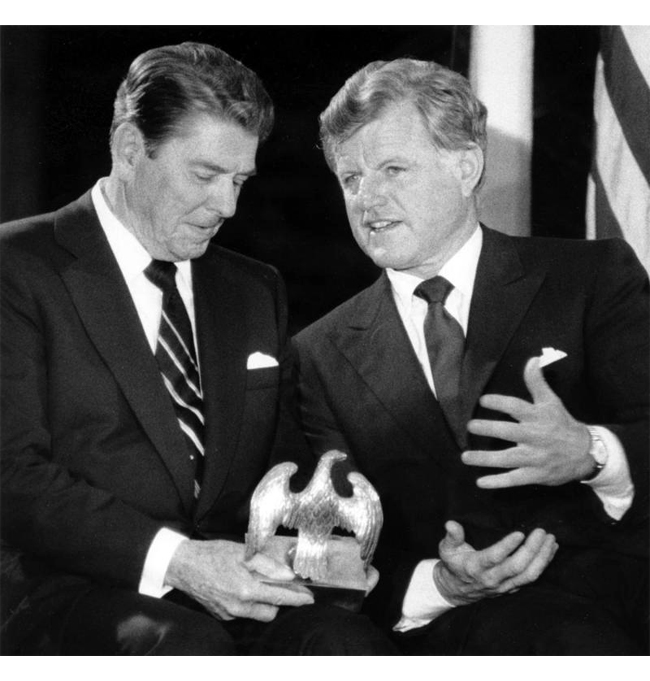

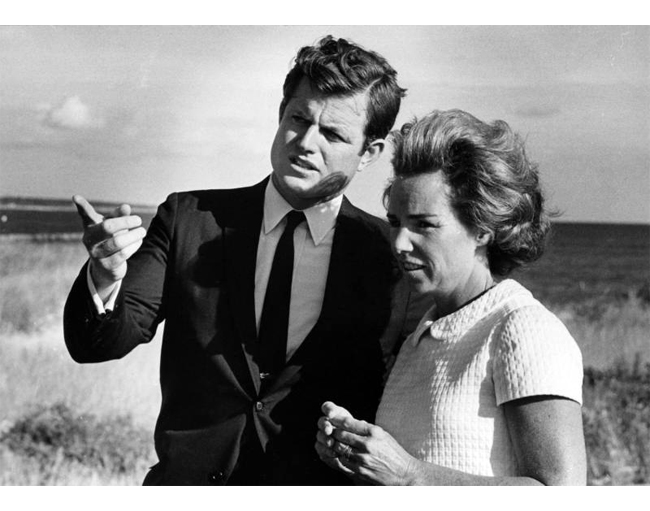

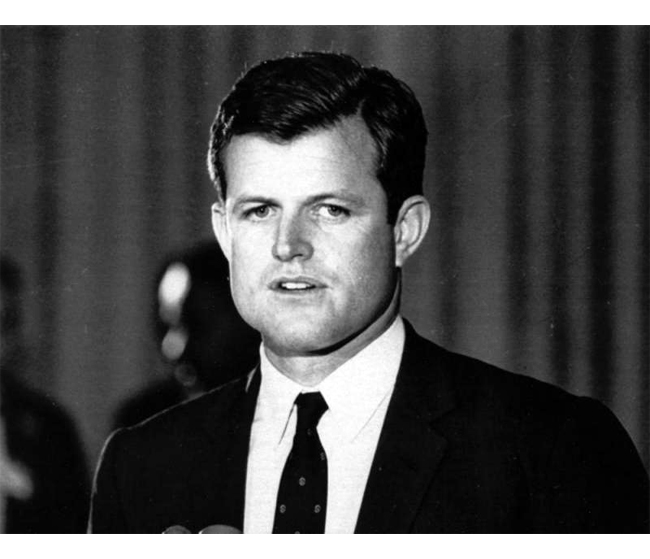

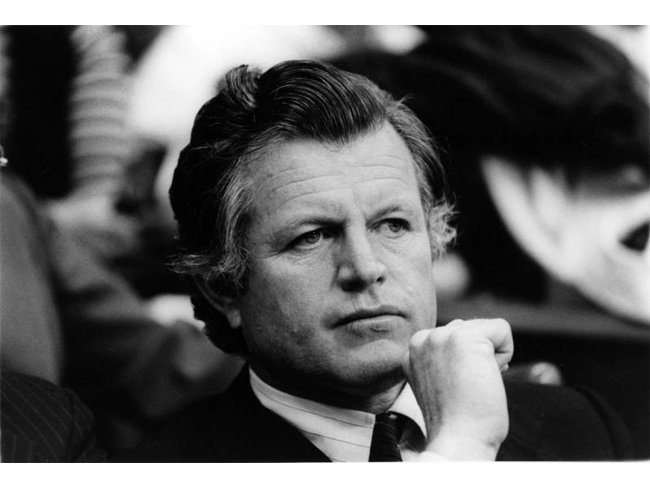

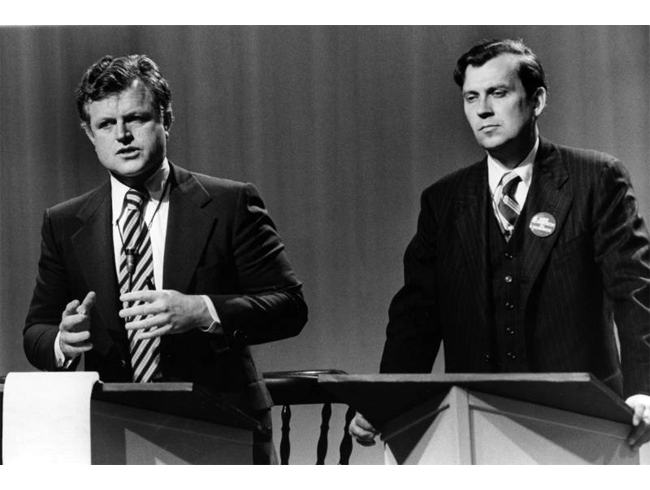

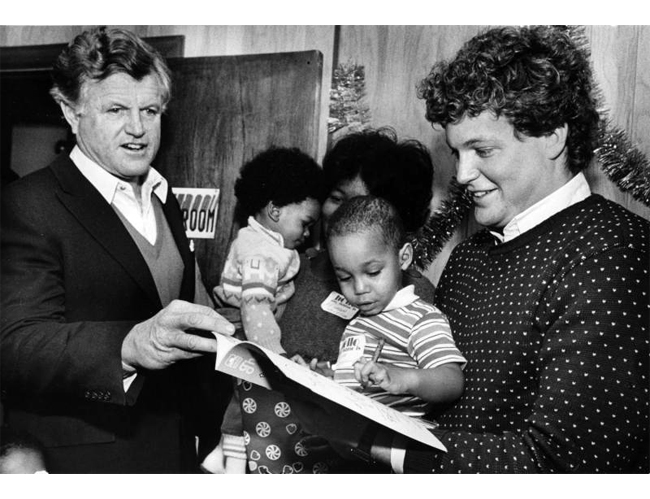

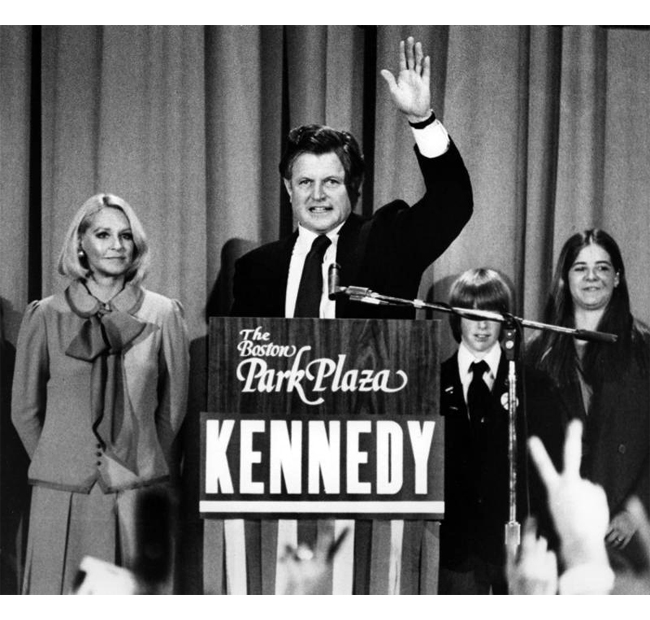

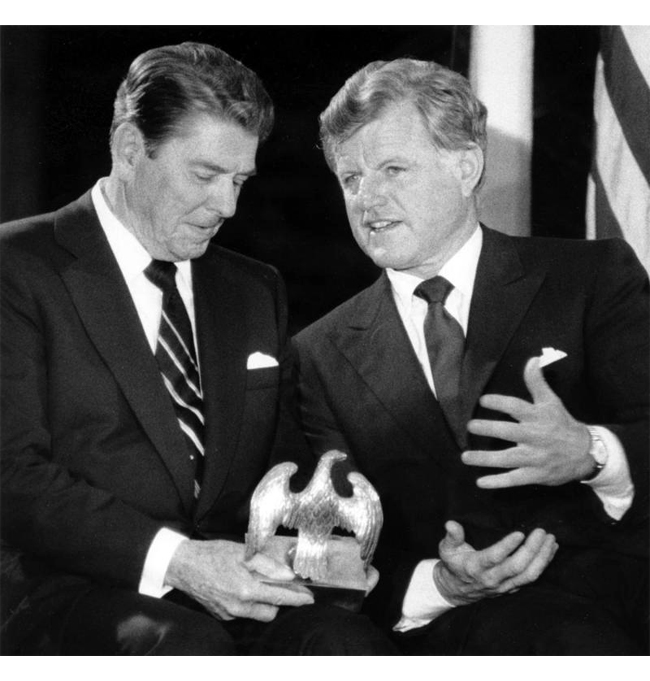

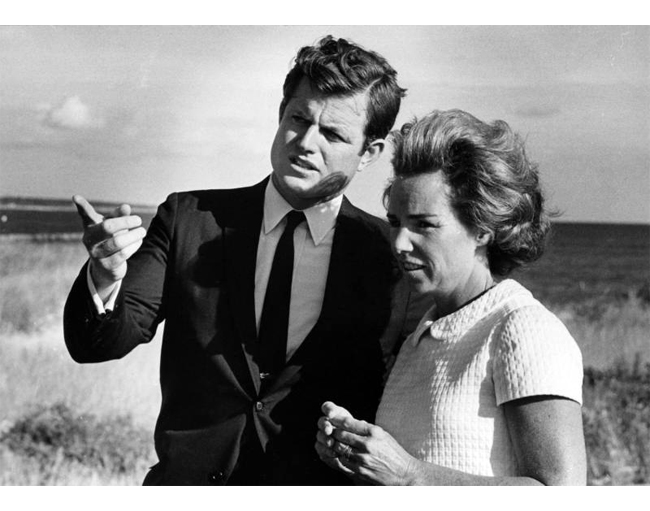

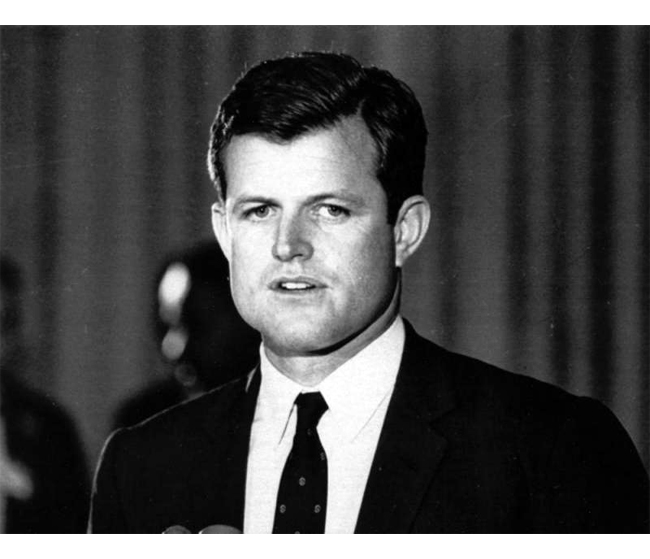

Vice President Joe Biden, voice trembling, paid tribute to one of his closest friends, Sen. Edward Kennedy, calling him a “truly remarkable man.” “Today, we lost a truly remarkable man,” Biden said. “To paraphrase Shakespeare, I don’t think we shall ever see his like again. I think the legacy he left was not just with the landmark legislation he passed but in how he helped people look at themselves and look at one another. Kennedy spent a lifetime working for a fair and more just America … And for 36 years, I had the privilege of going to work every day and literally … sitting next to him and being a witness to history every single day the Senate was in session.”

Kennedy’s optimism about America’s future was infectious, Biden said, often speaking haltingly and struggling for composure. “He was never defeatist. He never was petty. He was never small,” Biden said. “In process of his doing, he made everybody he worked with bigger — both his adversaries and his allies.” When people look back on Kennedy’s nearly half-century as a senator, “I just hope we remember how he treated other people and how he made other people look at themselves and look at one another. That will be the truly fundamental, unifying legacy of Teddy Kennedy’s life … .”

Rest in peace Senator. The fight is over.

Text and images sourced from UPI.

Tags: Tribute

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Tuesday, 25 August 2009

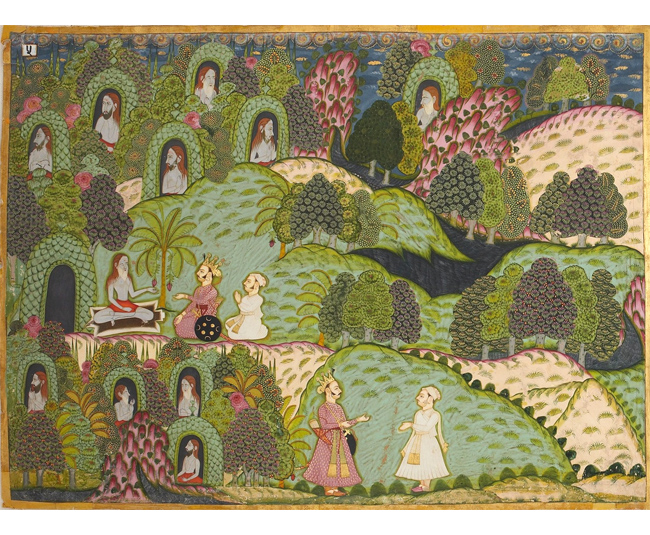

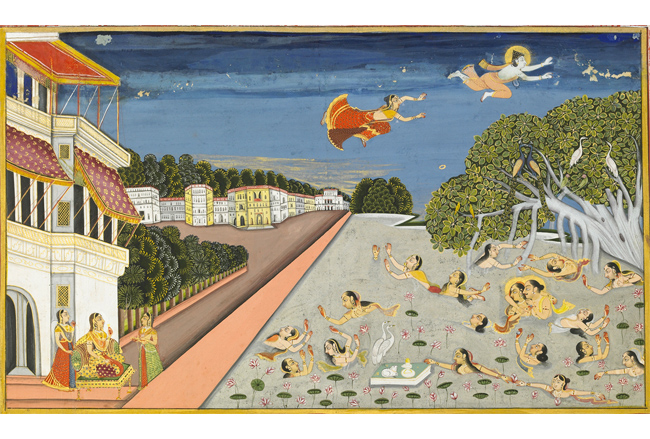

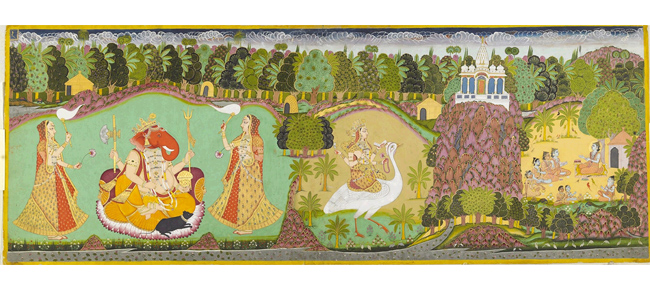

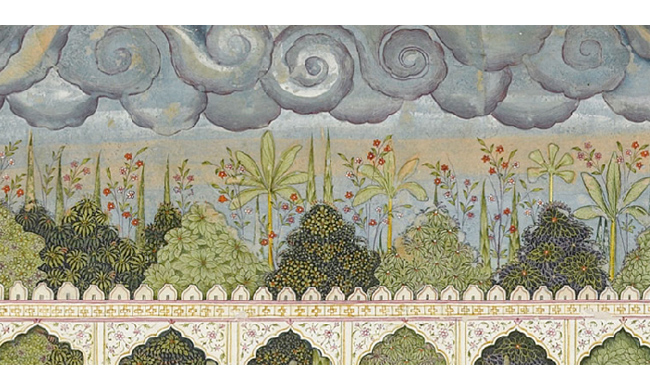

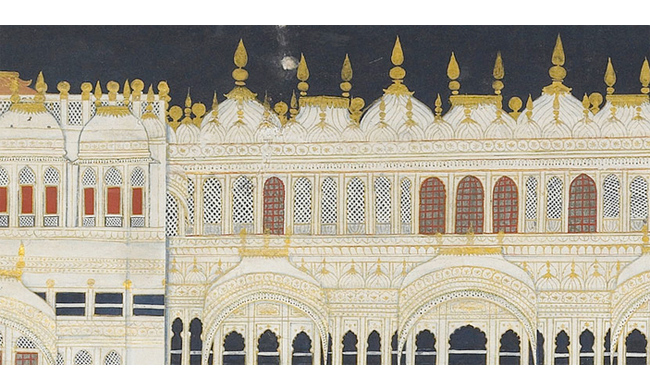

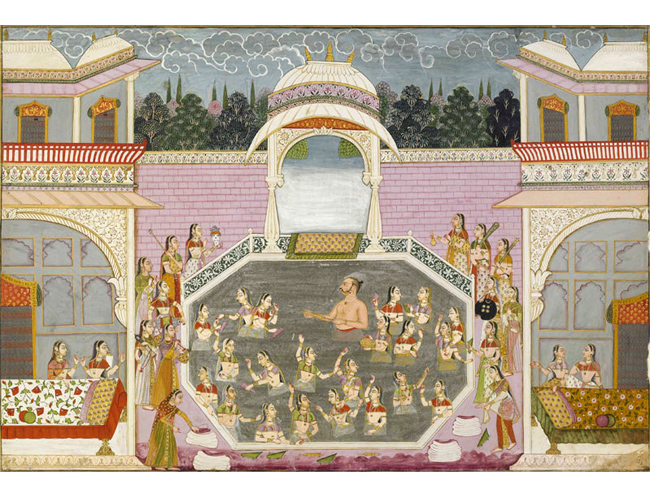

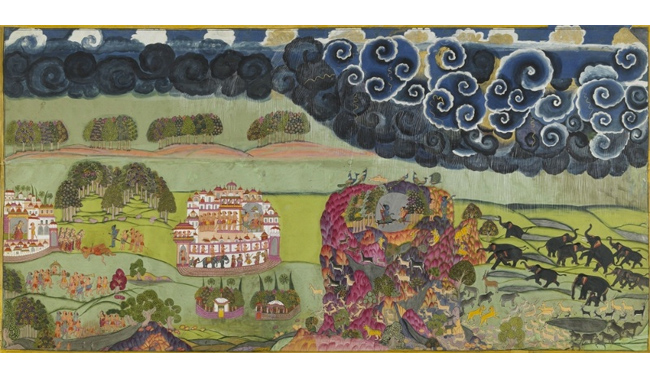

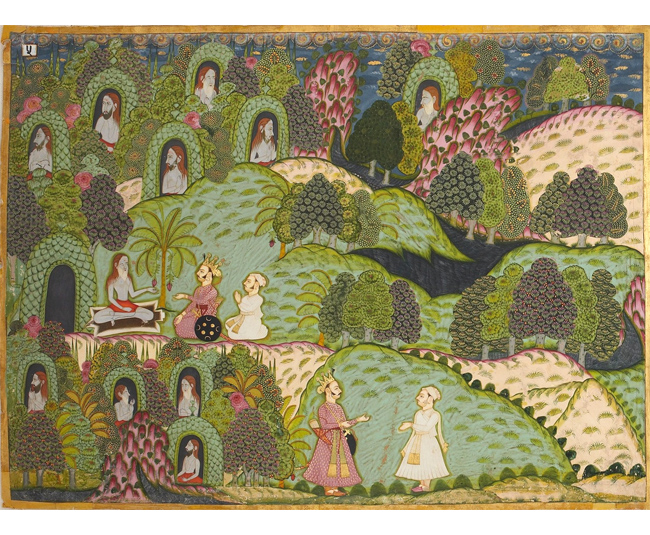

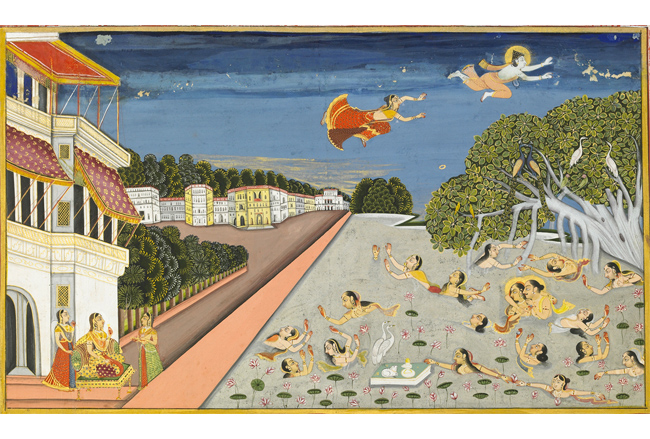

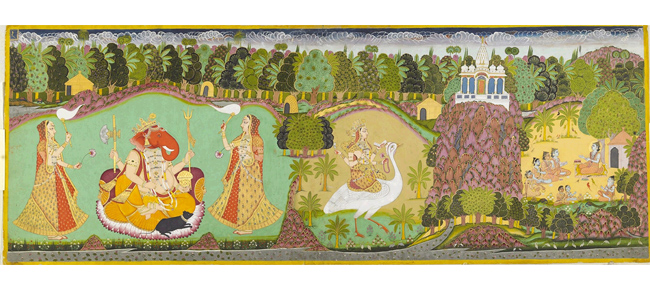

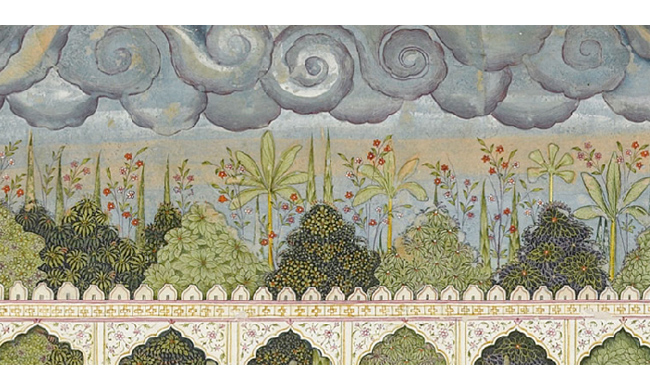

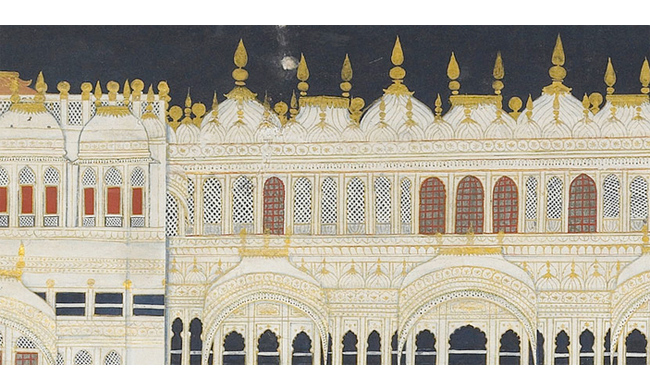

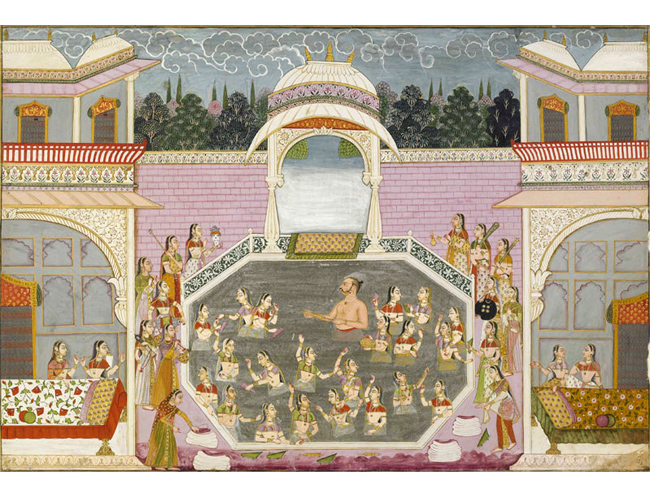

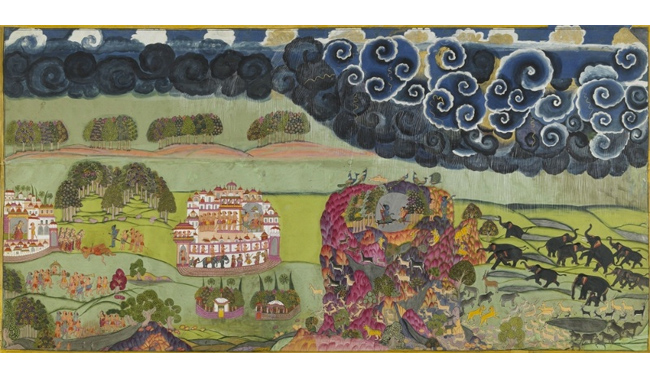

Two hundred years ago, the little Indian kingdom of Marwar, in what is now Rajasthan, was a bloodsoaked and troublesome place. The long decline of the Mughal empire encouraged squabbles in the Hindu ruling dynasty; in 1751 an upstart second son, Bakhat Singh, came to power, having murdered his father the maharaja a quarter-century earlier. But the upheavals brought with them a creative revolution. Over the next century and a quarter, Marwar produced some of the most colourful, strange and shocking art on the subcontinent.

Bakhat Singh swept aside Marwari artists’ decorous imitations of Mughal miniatures. His artists were set to work on murals and large panel paintings showing the maharaja frolicking in palace courtyards and gardens with the ladies of his zenana, or harem. There is no hint of the bloodshed and instability that surrounded Bakhat Singh, who ordered himself portrayed not as a regal warrior, but as Marwar’s pre-eminent lover… When Bakhat Singh’s son Vijai Singh took the throne in 1752 (his father having been poisoned by a vengeful niece), Marwari art abandoned sex for devotion. Vijai Singh was highly religious, but his taste in art was anything but austere. His atelier in Jodhpur was ordered to create yet another new genre of painting: giant illustrations of episodes from the great Indian religious texts, to be displayed as poets recited the accompanying verses. The dizzying detail was intended to draw viewers into the direct contact with the divine sought by devotees of Krishna.

… The golden age of Marwari painting came to an end at the hands of the East India Company. In 1843, the expansion of British power forced Man Singh to relinquish his throne, and he withdrew to live as an ash-smeared yogi in a tent in Jodhpur. The power of the Naths was shattered, Man Singh’s atelier atrophied, and his heretical paintings were locked away in a Jodhpur fort, where they were recently rediscovered. Their first trip to this country is a rare chance to discover a long-forgotten tradition that Britain’s colonial ambition destroyed.

Text by Rachel Aspden. This collection is currently exhibited at The British Museum.

Tags: India, Painting

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Monday, 24 August 2009

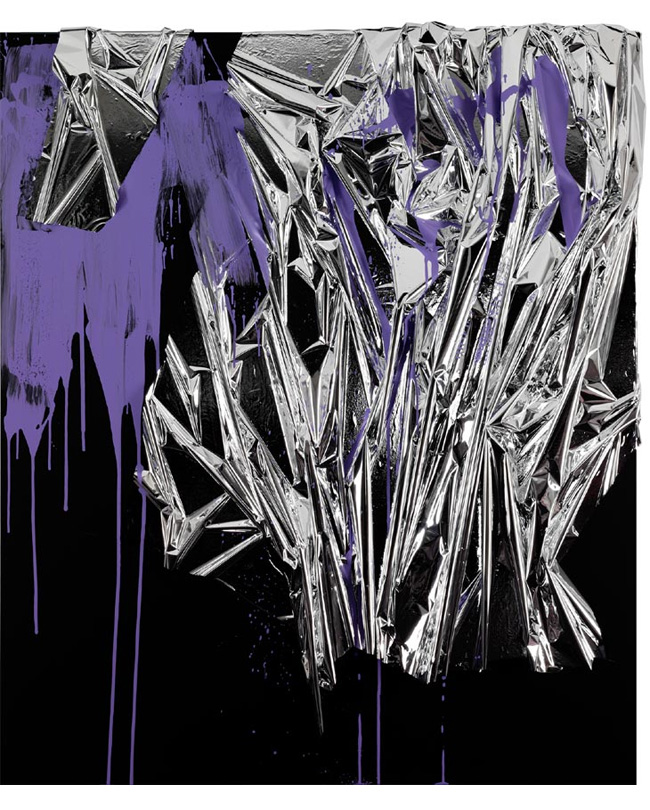

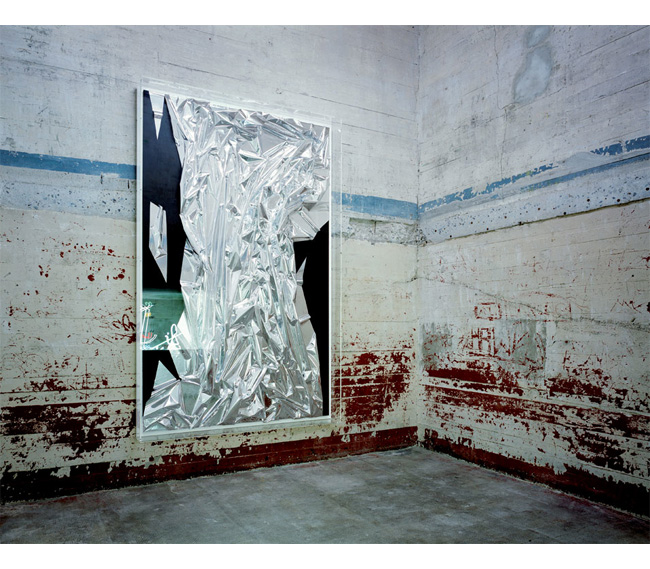

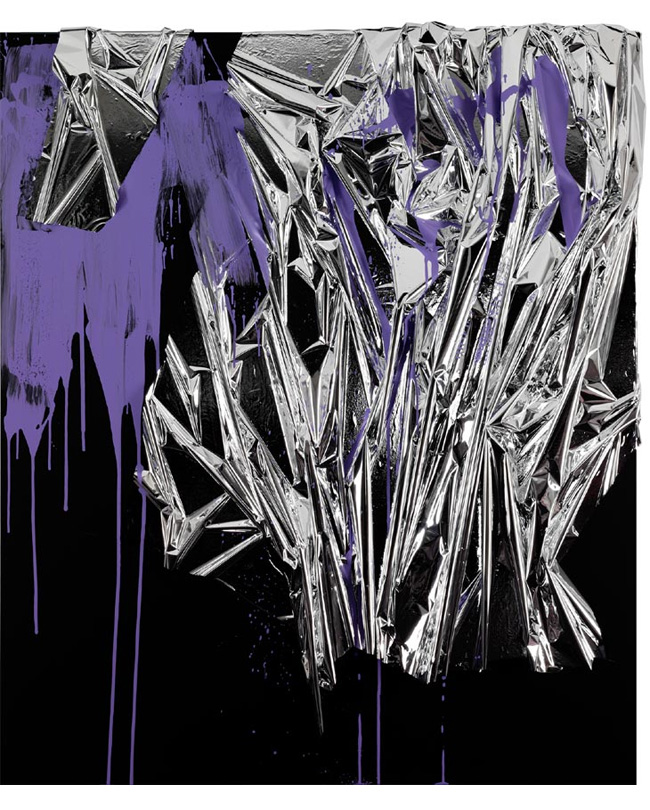

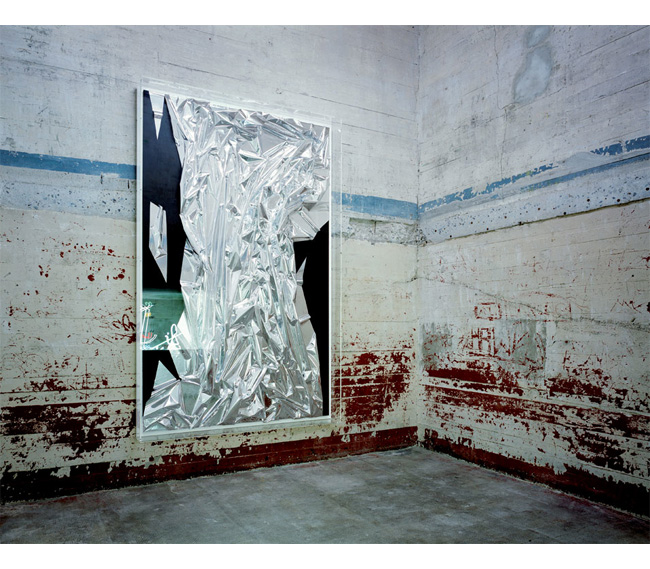

Through his paintings and sculptures, Gernman Anselm Reyle is reviving concepts of 20th century art history. He often cites the painter Otto Freundlich as a great influence. Minimal and abstract, Reyle’s works are notorious for eye-catching colors and surfaces. His paintings can be drippy, gestural or sharply geometrical, yet his works are related by their patterns and bold palettes. Stripes and kaleidoscope-like patterns are common compositional cliches that Reyle makes his own.

Although armed with an array of gestural brushstrokes, kitschy found objects and outdatedly ‘modern’ sculptural forms, Reyle skews his pieces away from their retro beginnings by yoking them with such futuristic materials as day-glo and fluorescent paint, neon light, silver Mylar and sheets of mirror. The results are futuro-modern, perhaps, or retro-contemporary. In 1964 Clement Greenberg despairingly described how painterly abstraction had become, in the hands of a watered-down second generation, ‘by and large an assortment of ready-made effects’ where ‘the look of the accidental had become an academic, conventional look’. Forty years later these ready-made effects are willingly taken onboard by a new generation, ready to dissociate them from their original contexts without the need for the self-conscious irony of their Postmodern predecessors. The drip, the pour, the stain, the gestural brushstroke all have a role to play in Reyle’s painting, as do monochromes, striped canvases and black and white Op geometricism lifted straight from Victor Vasarely. For Reyle the painterly gesture is there for the taking: it has the same potential ready-made status as a found sculptural object.

Introductory text adapted from Art Observed. All other text sourced from Frieze.

Tags: Painting

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Saturday, 22 August 2009

The work of George Condo is grotesque, comic, baroque and sinister. His paintings, drawings and sculptures portray humanlike figures that make one think of caricatures and cartoon films. But these characters are brought to life on canvas in an expressive utterly painterly manner. Condo goes about his work in the traditional way, with preliminary studies and paying a great deal of attention to shades of colour, light and brush strokes. His portraits blend art history with elements of pop culture to arrive at a complex whole that he himself describes as ‘artificial realism’. They depict a contemporary, painterly vision of western society.

Condo’s work exudes a contemporary emotionality while striving towards a new conceptualisation of classical painting. Superficiality, self-representation and subcutaneous fear despair are evoked in a masterly fashion. Condo treats human psychology as a diverse complex topic, fixing upon the emotional ambivalence of human expression. Staging, representation and simulation is also embedded in one pictorial story narrative.

Text adapted from Xavier Hufkens.

Tags: Painting

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Friday, 21 August 2009

Heaven, earth, water, and forests are the natural ingredients in Axel Hütte’s landscapes. The photographs stage a subtle play on the difference between nature and landscape. Here, ‘nature’ is the physical world which surrounds us while ‘landscape’ is nature as it appears to the observer.

Nature has always been the subject of participatory interest, and man’s view of it is as ever subjective. Arcadia, for example, is a region in Greece you could visit – and likewise a spiritual landscape in which the earth is more fertile, the sky brighter, and life full of milk and honey. How nature appears to man – be it georgic, heroic, pleasant or fearful – depends on his own sorrow or yearning informing his gaze. As civilization advances, our vision has become more sentimental. As inner harmony became lost, people have sought an environment that was intact. A wider horizon and a view of unspoiled places which manifest no evidence of the destructive hand of man promise flight from urban claustrophobia.

Hütte’s work is based on a strict visual language which is optically accurate and evidently neutral. Devoid of narrative and overt sentimentality, it seems to adhere to an ideal of photographic “objectivity” and veracity. His vision is one of precision and clarity. He approaches his subjects with a disciplined restraint that truthfulness of representation is never prone to doubt. In addition, he responds to the landscape with an unflinching respect for its morphological identity. (Katerina Gregos)

Introductory text sourced from Deutsche Börse Group.

Tags: Photography

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

Thursday, 20 August 2009

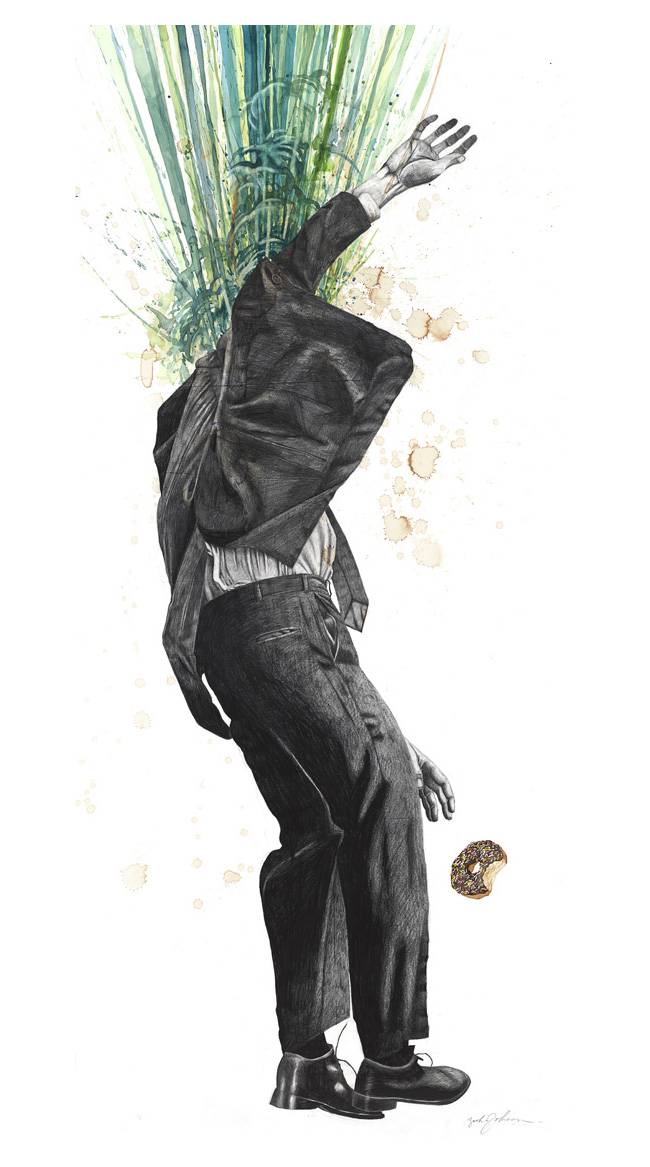

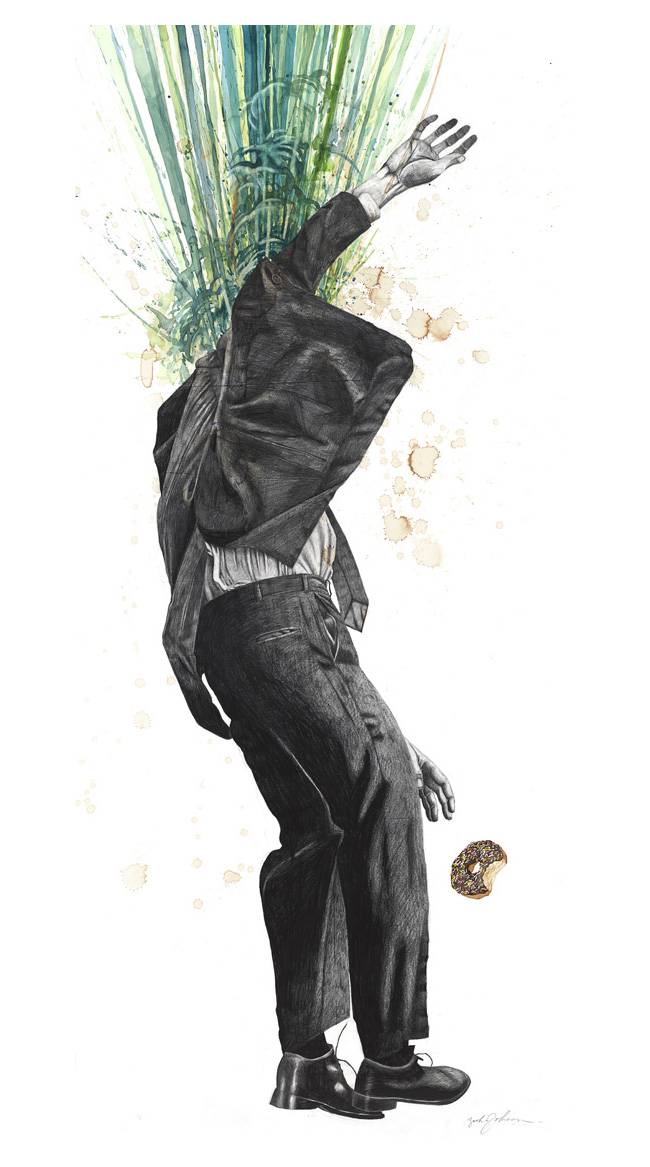

I used to doodle endlessly in class, especially during Biology. It infuriated my teachers but filled my classmates with curiosity. They always wondered what I would draw next. I never realised it at the time, but my doodles let me explore my inner world - a world filled with both biological possibilities and physical impossibilities. Looking back in hindsight, I now understand why I was very much a loner in school - I was that odd kid with dark unfathomable scribbles all over his notebook, the kid whose mind was constantly too preoccupied with his own thoughts to play soccer or swim. I have lost all those sketches now, but seeing Zach Johnsen’s work reminded me of my pastime. While I was certainly neither as talented nor as skillful as Johnsen, I think the sinister quality of his work really brought back memories of my childhood.

Tags: Illustration

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Wednesday, 19 August 2009

Delicate and elegant as they are, ancient costumes have alwways been a symbol of Chinese cultural tradition, as clearly witnessed in the 2008 Beijing Olympics Opening Ceremony. But as time passes by, that materialism and consumerisn gradually change the Chinese culture - Western style attire substitute traditional ones. By making a contrast between modernism and traditionalism, Beijing-based painter Peng Wei attempts to search for the Chinese cultural myth in today’s society.

As one of the younger generation of Chinese contemporary artists who have taken a decidedly modern approach to the use of classical techniques, Peng Wei’s work displays a profound knowledge of the Chinese ink painting tradition, which she insists is still alive and constantly changing. While Chinese robes may have become remnants of a bygone era, they appear in Peng Wei’s paintings charged with fresh narratives and contexts - an indication of the artist’s self-confessed fascination with the ‘lost and beautiful’ items of the past.

Text adapted from Plum Blossom.

Tags: Art, China, Painting

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

Monday, 17 August 2009

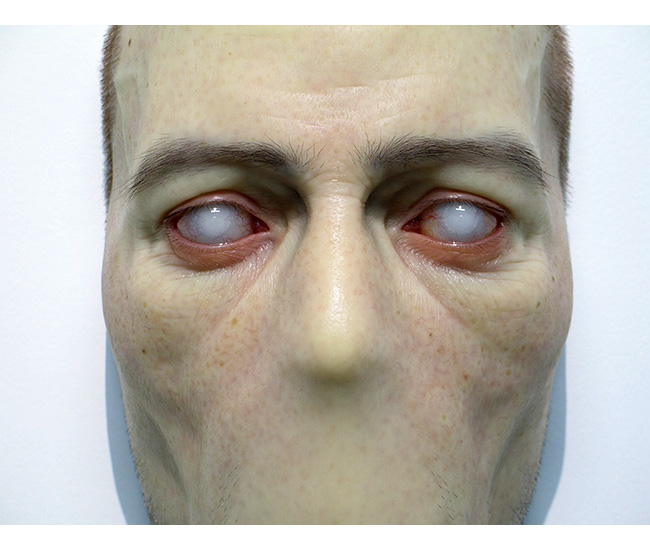

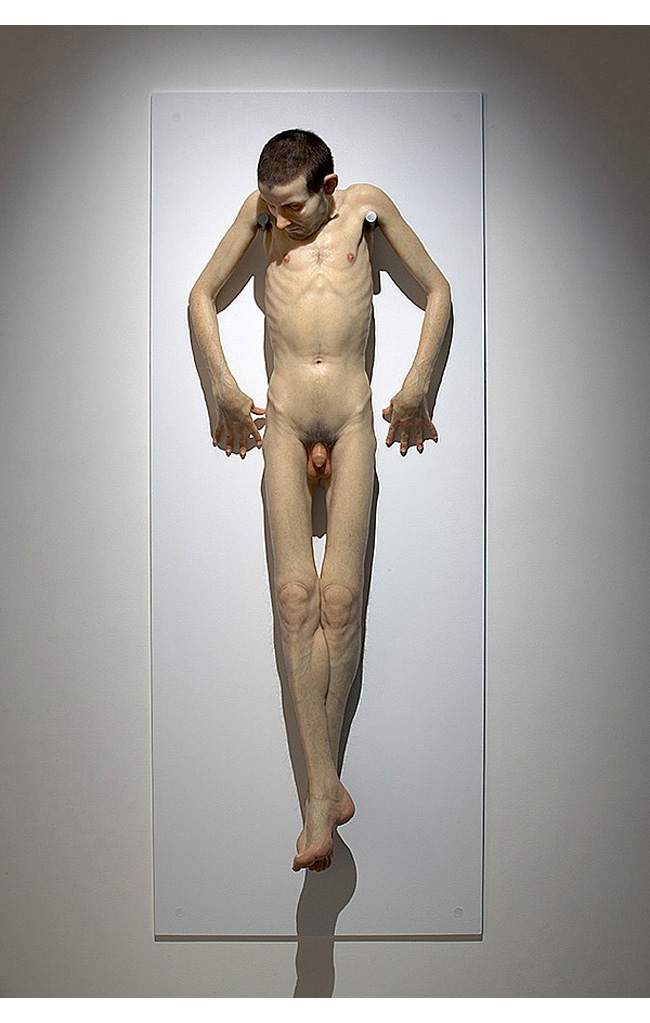

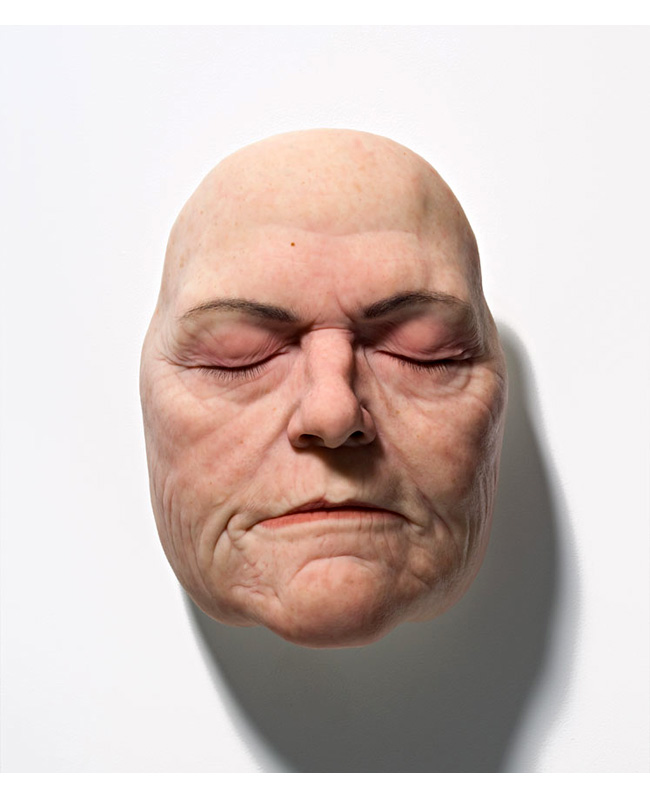

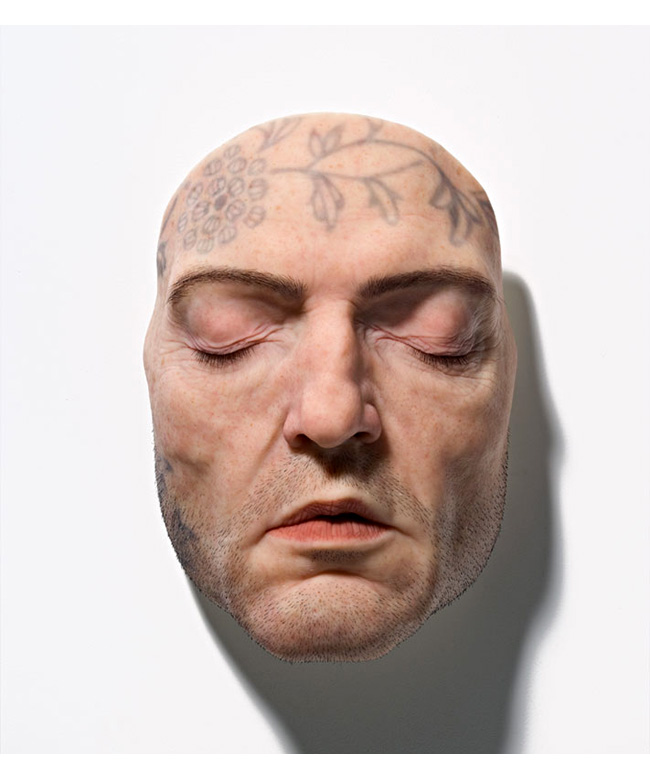

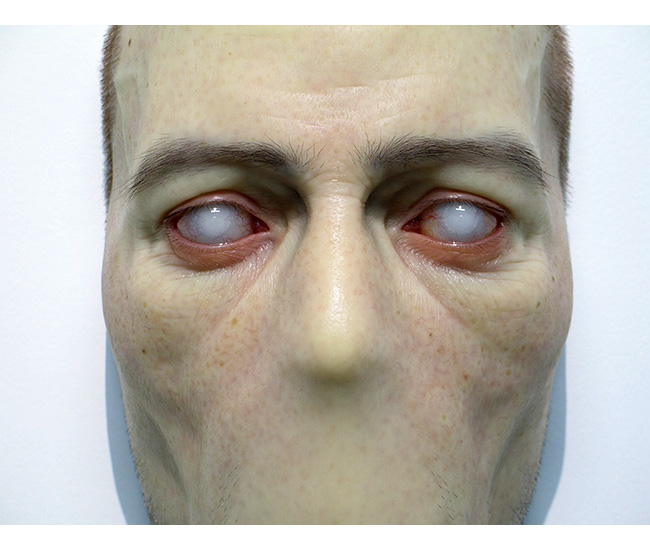

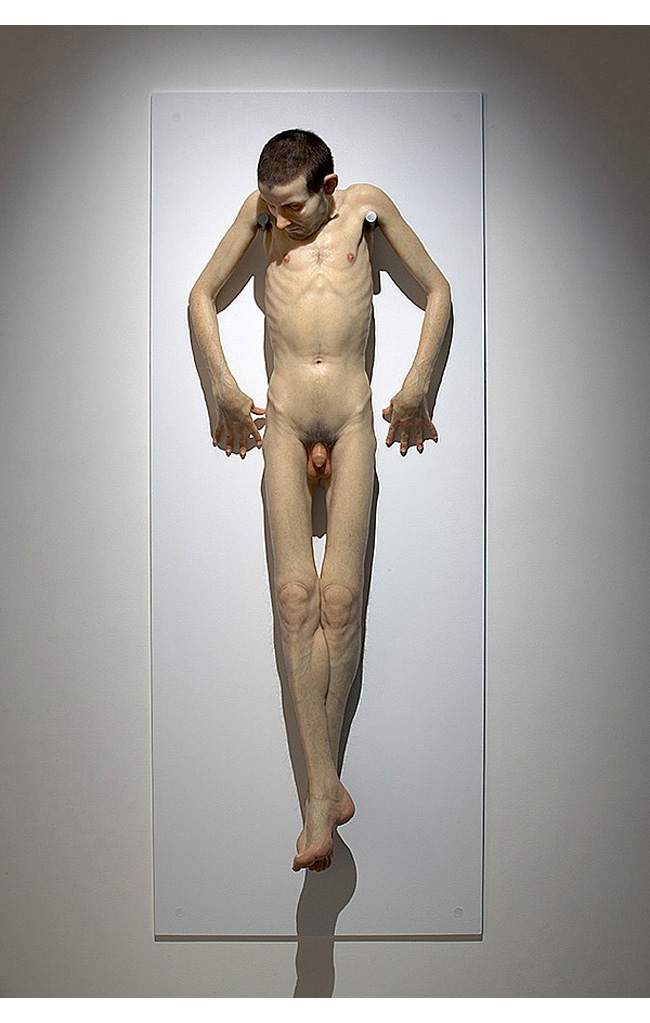

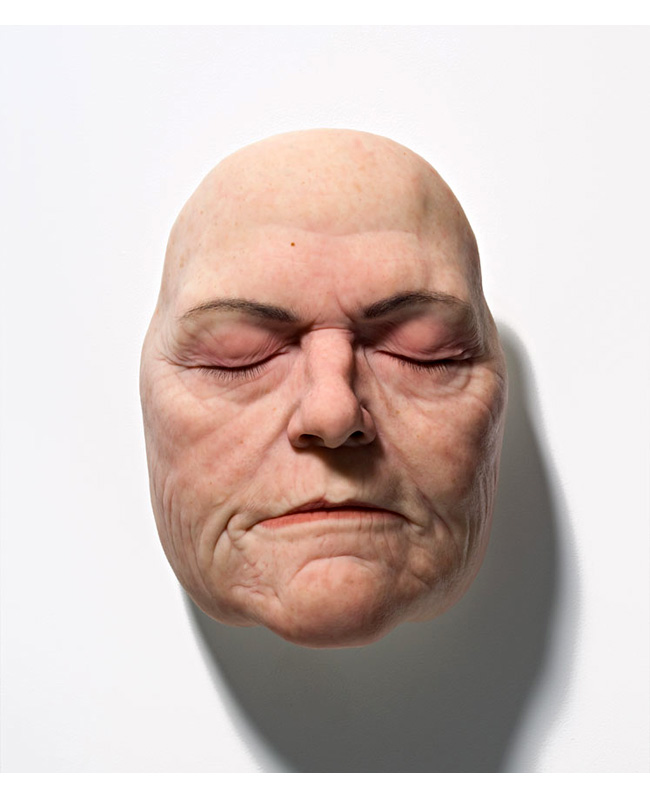

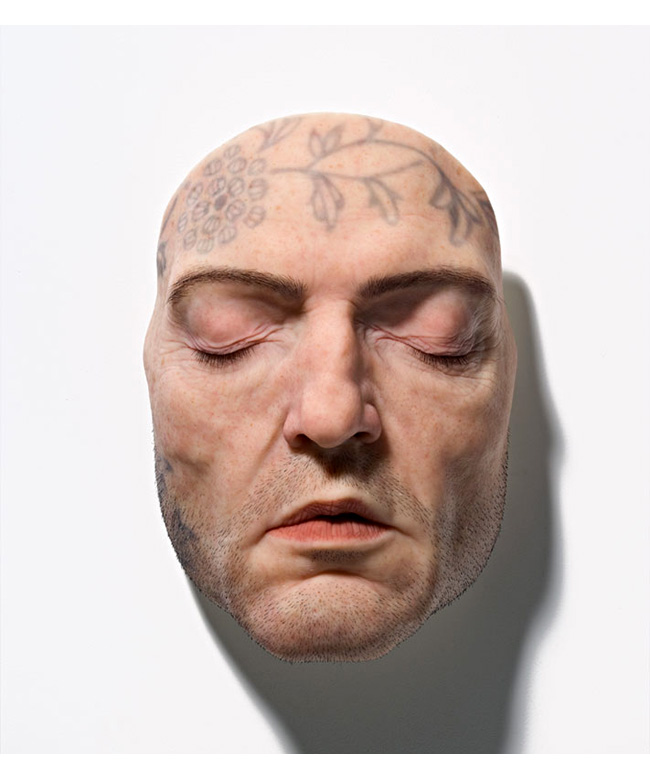

… A naked man is hung up by the armpits. The suspended man, with his drooping head and transcendent air of concentration, recalls the sacred archetype of Christ on the cross. It is as if, like Christ, he is hung up for maximum humiliation in a punishment that might be rehearsed in holy rituals for an obscure redemptive purpose. In another piece, a face of a man whose mouth has entirely dissolved into the flesh of the face, leaving a smooth and gentle volume between nose and bristly chin. The glazed eyes stand out with reddened thyroidal frenzy, almost as if expressing the suffocation involved in losing your nostrils and mouth…

The comprehensive level of detail, sinister as it may sound, border on utter obsession. The verisimilitude in the treatment removes you from the comfort of analogous images in the history of art. Australian hyper-realist sculptor Sam Jinks makes the skin look like skin, which is luminous and penetrated by light. You could imagine seeing pores and follicles if you took a microscope to the surface. His works have a powerful presence. And, like Ron Mueck’s work, he uses unsettling scale to create drama and induce emotions. In traditional aesthetic terms, Jinks’ naked hanging man is the wrong size. The figure is too small to be real, but too big to be a doll or figurine. The dwarfism with perfect proportions seems semantically inconvenient and disturbing when the figure turns real in your imagination. It is an embarrassing size for a man to have, as the mature body has the scale - but not the shape or detail - of a boy’s body.

Adapted from Robet Nelson’s review.

Tags: Art, Sculpture

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

Friday, 14 August 2009

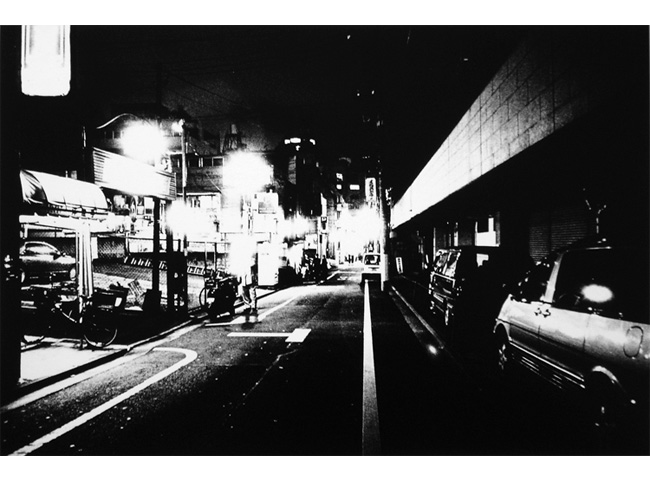

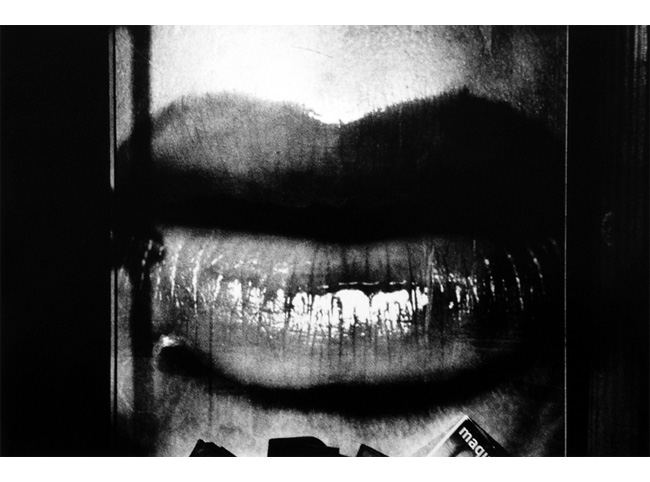

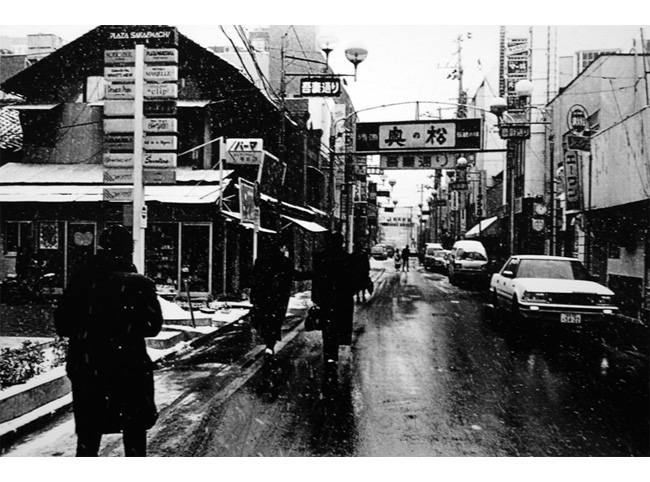

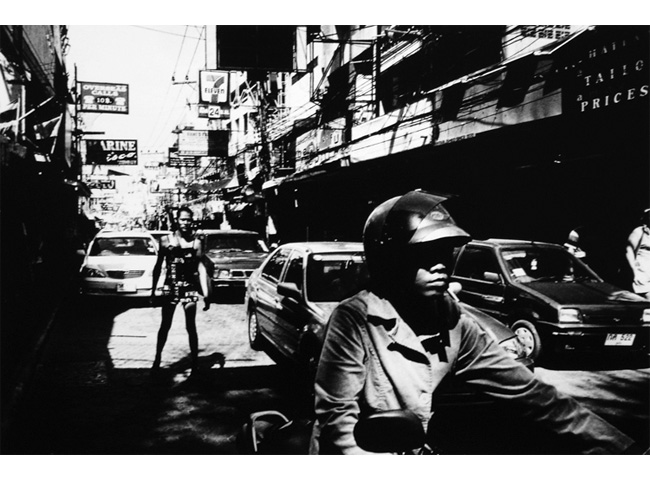

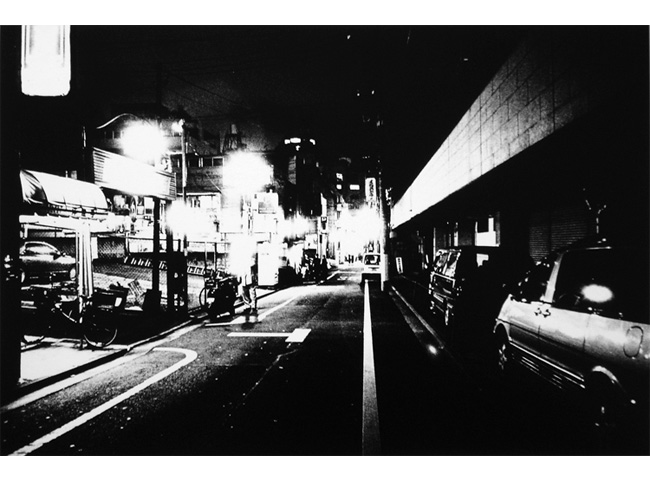

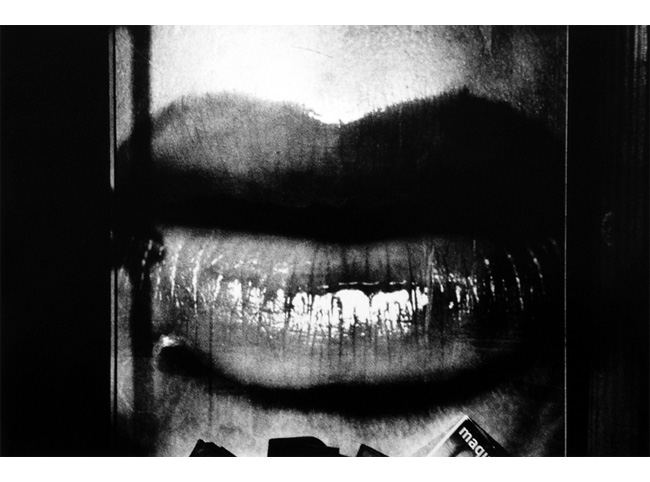

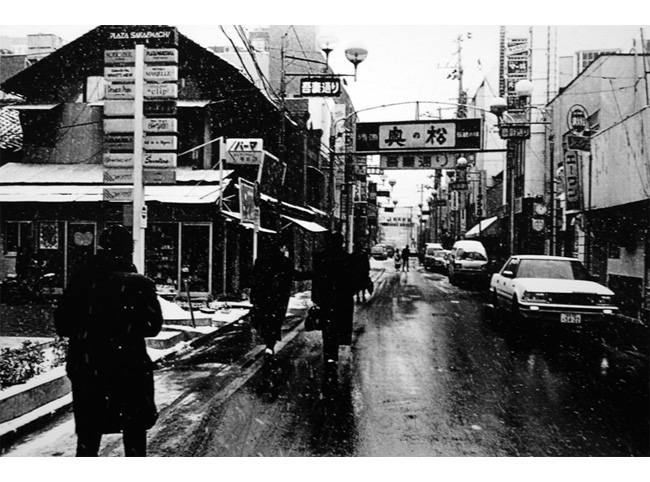

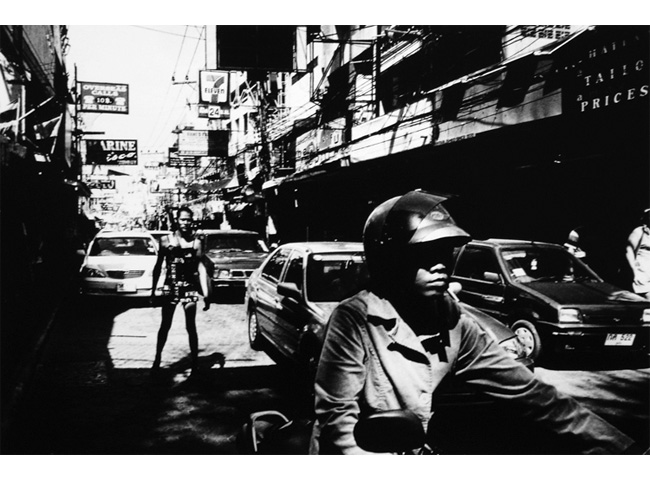

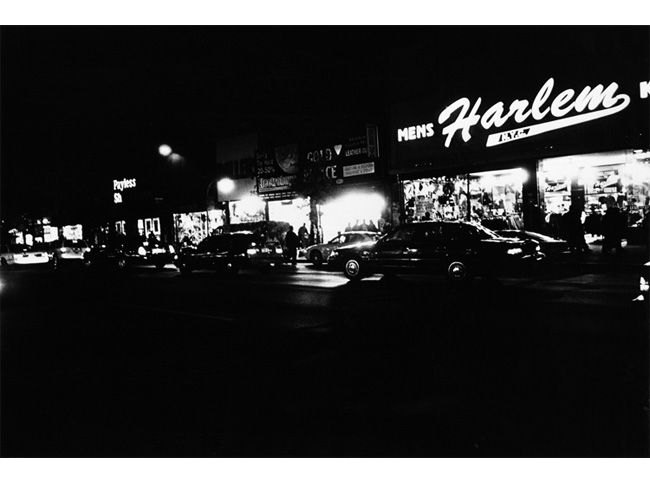

Daidō Moriyama was born in 1938 in Osaka. He is easily one of the most important Japanese photographers since 1945. His work, depicting the breakdown of traditional values in post-war Japan, plays a central role in establishing Japanese photography as one of the most creative directions in the history of photography. His work was often stark and contrasting within itself. One image could convey an array of senses; all without using color. His work was jarring, yet symbiotic to his own fervent lifestyle. The photographs shown here are from the ‘Kyoku / Erotica’ series and reflects Daido Moriyama’s ambivalent perception of the world. For Moriyama, the world is both a danger zone and a minefield of sexual tension, a mixture of danger and allure.

“Moriyama is conspicuous for the brutality with which he distorts photographic description: his pictures are sooty with grain, blotchy with glare, often out of focus or blurred by movement, often defaced by scratches in their negatives. Because Moriyama is often looking through some barrier — steamy glass, a grille, a hole in a door –o ne may begin to squint a little before realizing that the picture will never get any clearer. None of this represents bad technique. It is wholly purposeful, and gives the photographer an expressive leverage perfectly adjusted to his subjects: if the actor impersonating a geisha was already grotesque before Moriyama arrived, the distortions that the photographer adds in evoke the shock of discovering him. Many of Moriyama’s pictures thus hit us doubly — with a frightening or repellent thing, and with a manner of rendering it that is the visual equivalent of nausea, vertigo or horror.” (Leo Rubinfien)

Introductory text adapted from Priska Pasquer.

Tags: Japan, Photography

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »